Jason Foster’s new book, Defying Expectations, is an account of the resilient United Food and Commercials Workers Local 401, a union that defied the odds in Alberta, a province that previously had some of the most antiunion labour laws in Canada. Defying Expectations revisits some of Alberta’s most unforgettable strikes—from the 1997 Safeway strike to the 2002 Shaw Conference Centre strike and the 2005 Lakeside Packers strike. Through the labour movements organized by UFCW Local 401, Foster shows that unions have the capacity for meeting the challenges of the twenty-first century workplace.

The certification of the Lakeside Packers beef-processing plant in Brooks, Alberta was a historic victory for UFCW Local 401. The excerpt below outlines Foster’s personal experience walking the picket line and how it inspired his new book.

No Ordinary Strike

In October 2005, I spent a day walking the Lakeside Packers picket line. The beef-processing plant was in the midst of an ugly first-contract strike. During my tenure as a staff member for the Alberta Federation of Labour (AFL), I had walked my fair share of picket lines. In my experience, they are mostly the same: workers milling about, chatting idly among themselves, stopping vehicles and pedestrians to explain the dispute, and occasionally rallying to stop strikebreakers from crossing the line. In the world of modern labour relations, the angry energy once associated with strikes has largely been drowned in a sea of legal restrictions. Laws governing picket lines, intrusive video surveillance (practiced by both sides), and labour board injunctions generally serve to keep expressions of outrage and protest in check. More the stuff of monotony than excitement, the modern picket line resembles its early-twentieth-century ancestor only in the presence of picket signs.

However, the Lakeside strike was no ordinary strike. The plant is located in Brooks, a sleepy southern Alberta town previously known for cattle and oil well servicing and deeply entrenched in Alberta’s conservative rural culture. The employer, Tyson Foods, was virulently antiunion and had fought hard for two decades to keep the plant union-free. After a previous failed organizing bid, the company had taunted the union by hoisting a banner on its sign beside the Trans-Canada Highway declaring the plant to be “Proudly Union-Free.” Then there was the union involved in the strike—United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) Local 401. A grocery store local, representing mostly food-related service sector workers, might seem an odd choice of candidate to take on this Herculean fight, especially when another Alberta local, UFCW Local 1118, already predominantly organized and represented meat-packing workers. What did grocery workers know about the tough work and brutal conditions of a meat-packing plant?

But what made Lakeside truly different, at least for me, was the workers. In keeping with industry trends, the composition of the workers at the Brooks plant had shifted dramatically, in the wake of an ongoing influx of African and Asian immigrants (see Broadway 2013). Half of the plant’s workers hailed from southern Alberta or other rural areas of Canada, while the other half came from Somalia, Ethiopia, Uganda, Sudan, the Philippines, and other far-flung locations.

It was a plant divided and a town in flux. I knew before I arrived in Brooks that the certification, gained by the narrowest of margins, was heavily split along racial lines, with the Canadians by birth largely opposed and the newcomers in favour. I also knew that the latest drive had been sparked by a wildcat protest (an unofficial, unsanctioned walkout) by a cluster of Sudanese workers: this time, the union had found a way to win over the newcomers.

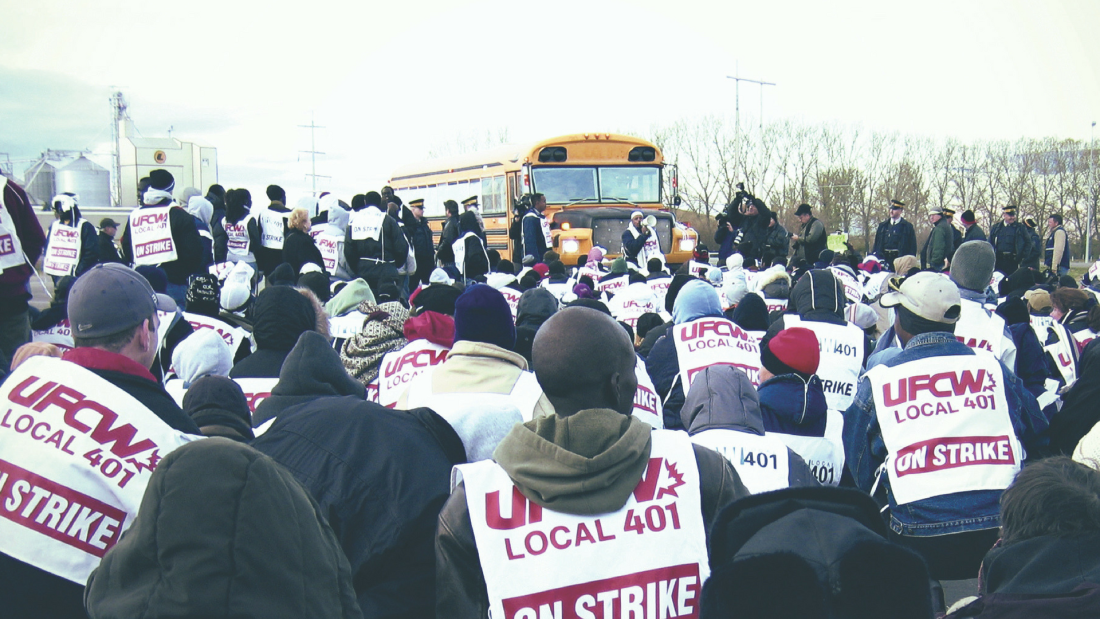

I had been told that the strike was not pretty, but that warning hardly prepared me for what I experienced on the picket line. It was a crisp fall day but the sun was shining. Just off the highway, at the main entrance to the plant, clustered hundreds of workers wearing UFCW Local 401 bibs, some standing around fire barrels, others meandering across the road, still others talking in small groups—and almost every single face was black or brown. I had never been on a picket line like this. Until now, the labour movement in Alberta had been pretty “white” (Alberta Federation of Labour 2001).

Amidst the sea of African and Asian newcomers, I spotted a handful of UFCW staffers familiar to me. But even those I didn’t know I immediately identified as union staff, not because of the colour of their skin (the line that day included a few workers from Newfoundland), but because they seemed so different in every way from the people for whom they were working. The staffers were a mélange of young, energetic grocery store workers and grizzled union vets with years of experience in the labour relations trenches. Neither group seemed to have anything in common with the men and women milling around them.

Then the local president, Doug O’Halloran, drove up to the line. The energy in the crowd rose. O’Halloran, a larger-than-life former meat packer, carried himself with an air of authority tinged with modesty. After some informal greetings, he addressed the crowd. They listened, rapt, cheering and applauding everything he said. I was surprised at the enthusiasm, energy, and, yes, love they expressed for him.

Later that day, the employer tried to push some buses filled with scabs through the line. Things got crazy fast. No polite discussions here. Shouting and jeering, the picketers rocked the buses as they tried to inch their way through the sea of people. The members and staffers acted as one, unified in conviction and action. The energy was electric and vaguely dangerous. A few buses got through, while others gave up and turned away. Soon the swell ebbed and the line calmed down. It was a partial victory, but there were more battles to come.

Download Defying Expectations for free on our website.

References

Alberta Federation of Labour. 2001. “The State of the Unions: Trends in Unionization in Alberta.” Edmonton: Alberta Federation of Labour.

Broadway, Michael. 2013. “The World ‘Meats’ Canada: Meatpacking’s Role in the Cultural Transformation of Brooks, Alberta.” Focus on Geography 56 (2): 47–53.