In light of the tragic events that have occurred in our world over the past few months, we would like to share the wisdom of one of our authors, Patrick Grant, whose book Imperfection provides the reader with an analysis of the rise of religious extremism across the globe. The chapter reproduced below, “Talking to the Cyclops: On Violence and Self-Destruction,” is a timely discussion of how violence effaces language and identity.

Talking to the Cyclops: On Violence and Self-Destruction

by Patrick Grant, a chapter from the book Imperfection (AU Press, 2012)

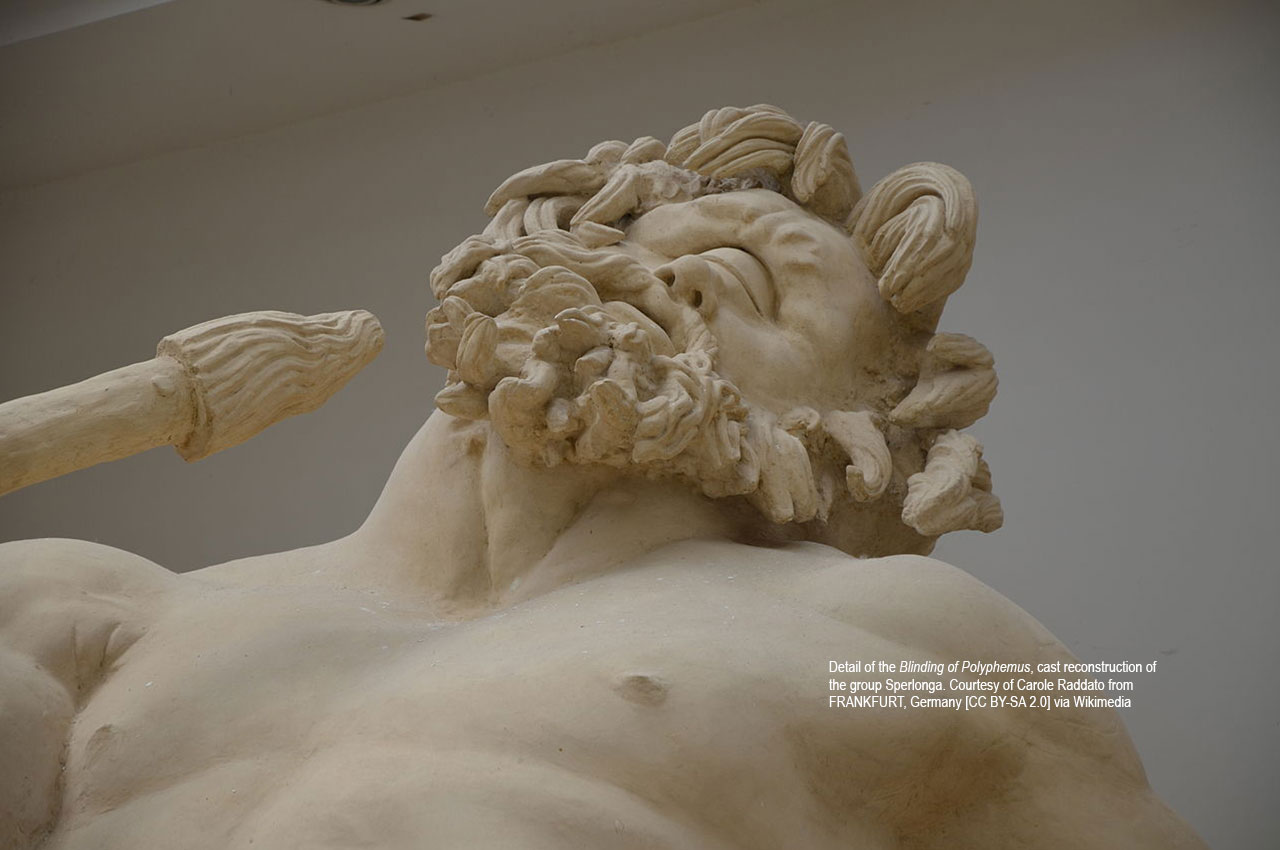

Here, I want to consider a little further — again with some passing reference to Northern Ireland — the fact that in robbing its victims of personal identity, violence is also self-destructive. As the French philosopher-theologian Simone Weil says about the use of force: “To the same degree, though in different fashions, those who use it and those who endure it are turned to stone.” She wrote these words in an essay on Homer’s Iliad, and to pursue the idea that violence dehumanizes both victims and perpetrators, I would like to consider an episode in Homer’s other great epic, The Odyssey.

On his return home after the Trojan war, Odysseus and his crew stop at an island near a land inhabited by one-eyed giants called Cyclopes. These creatures live in isolation from one another and have little knowledge of human community, relationship, or hospitality. Odysseus visits the cave of one of them, Polyphemos, but when Odysseus makes an introductory speech, Polyphemos does not answer. Instead, he picks up two of Odysseus’s twelve companions by the heels and smashes their brains out on the floor, “like killing puppies.” He then devours the dead men and rolls a giant boulder across the mouth of the cave to prevent the others from escaping. Later, he devours two more men, and gets drunk on the wine Odysseus had brought as a gift.

As the Cyclops lies deeply asleep, Odysseus and his remaining crew prepare a wooden stake, hardening the sharpened point in the fire, and then ramming it into the Cyclops’s eye. The blinded Polyphemos rolls back the boulder to seek help, and by and by Odysseus and his men escape. As he sets sail, Odysseus tauntingly reveals his name (he had concealed it earlier) and mocks at his distressed and raging enemy. But the elated Odysseus has not fully considered that the Cyclops’s father is Poseidon, god of the seas on which Odysseus must sail. The vengeful Poseidon — able now to identify his son’s enemy by name — ensures that Odysseus’s journey is disastrous, filled with misfortune, wreckage, and death.

Clearly, there is no talking to Polyphemos, bent on violence: no appeal could be made that would not merely confirm the terrifying gap between language and the sudden, shocking deaths of the men. Yet, equally clearly, Polyphemos does not imagine the consequences of his actions for himself. He is blinded physically, not least because he is already blind to the fact that violence begets violence unpredictably.

For his part, the altogether-too-smart Odysseus, whose desperate resourcefulness has saved the day, cannot contain himself, and his triumphalist bragging ends up eventually costing the lives of his entire crew at the hands of Poseidon. Like the primitive weapon he used in the cave, Odysseus’s mockery is crude, turning the Cyclops into an object of contempt, just as the crewmen were nothing more than puppies to the Cyclops. In short, violence on both sides — whether we condone it or not — depersonalizes, and when it occurs, language either fails or is debased. Moreover, in response to the invasion of archaic terror and disorientation that violence brings with it, Polyphemos and Odysseus, not surprisingly, appeal to the gods — to Poseidon (for vengeance) and Athene (for deliverance).

Homer’s ancient story is not just an engaging fiction; it is exigent, telling us that we cannot talk to the Cyclops who has decided on violence, and if we do it won’t matter. This is because speech involves relationship, requiring mutual understanding, but violence depersonalizes and silences its victims. Today, paramilitaries wear masks and their victims are blindfolded or otherwise “disappeared.” In Northern Ireland, the Shankill Butcher, Lenny Murphy, finished off one of his victims with a spade, smashing in his face after having first removed his teeth with pliers. The killers of ex-IRA member Eamon Collins mutilated him and seem to have run a car over his head to finish the job. The effect in both cases was to render the victim faceless and voiceless — not a person — by an extreme objectification, the ferocity of which betrays how desperate is the anxiety to conceal or obliterate the fact that your victim is your fellow creature, a person like yourself.

In turn, such anxiety is often so powerful that God needs to be called upon to allay it. Thus, a pamphlet entitled Is There Room in Heaven for Billy Wright? was issued by supporters of the Loyalist Volunteer Force (LVF) founder after his death. Of course the authors assure us that there is room in heaven for Billy and that the faithful should follow his Christian example. Presumably, in his celestial quarters Billy at this moment is graciously enjoying the company of his erstwhile mortal enemy, Bobby Sands, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) hunger striker whose Christlikeness was proclaimed with equal conviction by his backers. God, it seems, takes care of Billy and Bobby together, and they are condemned now to love one another for eternity. Meanwhile, the tribal factions on earth will, according to taste, go on consigning each of them to eternal perdition — that further grotesque idea produced out of the apparently bottomless human capacity for rage, vindictiveness, and cruelty.

Mutual accusation along such lines becomes rapidly as futile as the muddled and contemptible actions that have given rise to it and to the further primitive superstitions brought to bear by way of obfuscation and excuse. Meanwhile, the violence goes on replicating itself with the same predictable unpredictability. Yet, as it happens, the Greek thinkers who tried to make sense out of the issues raised by Homer’s epics ended up also giving to Christianity a conceptual apparatus that has helped to explain the Bible — that compendium of books not without its own collusions in foisting human psychopathic behaviour upon God. Still, at best, the confluence of the Hellenic and Biblical traditions can also offer an antidote to their own disturbing witness to the worst that humans do.

Thus, if God is love, as John assures us (1 John 4:16), and if we think about this claim with respect for the conceptual consistency that philosophy prescribes, then it follows that God does not hate and is not vengeful. You cannot be love and express hate. Therefore God does not have enemies (this is true whether God exists or not), and even though you and I might make God (or the good) our enemy, it is folly to claim that God hates us back, or hates our enemies as we do (whether Billy or Bobby). In this view, the phenomenon wrongly described as God’s wrath can be nothing other than our own anger and hatred experienced in the light of what love and the good really are — in short, the hot stake of our own hatred being driven back into our own eye.

When alienation and anger are displaced onto God it is indeed a good deal easier for people to get on with destroying their enemies, calling them God’s enemies, but this self-deception requires such people to ignore a further basic point on which Christian theology insists, namely that God is a community of persons — three of whom constitute the Trinity. Whatever else God might or might not be — empty category or omnipotent creator — matters nothing in comparison to the only certain thing, which is that we find our good in and through persons in relationship, persons in community. To work with that principle in mind, aiming to shape a society in which the personal is political, is, in the end, the only way to mitigate the petrifying alienations that produced Polyphemos in the first place. The chances then at least are better of enabling the growth and development of individuals with whom we might talk, person to person. If the intention is good, Matthew tells us, then our whole body is filled with light because we see with a single eye (6:22). The unpredictable then is less likely to take us by surprise, even though it is prudent to remember that, short of the good society and without sufficient good fortune, the Cyclopes spawned in the wastelands of alienation and in the ghettoes of heartless privilege will still have us for dinner, without a word.

Need more?Read the whole book here.